|

Vittorio Carvelli

The Story of Gracchus

LIBER II (The Second Book)

Chapters 13-18

XIII. Aurora nova

13. A New Dawn

Gracchus remained cloistered in his study for the rest of the day, seeing no one, not even Terentius. He retired late, but was unable to sleep, his mind troubled by the disturbing contents of the prophecy that had been given to him by the god Apollo, through his oracle, the Sibyl.

As the first rays of the morning sun turned the sky a delicate pink, Gracchus rose from his bed and went down, accompanied by two of his young bodyguards, to the peristyle where the almost finished statue of Apollo had been placed. The marble was still in the process of being polished, and the god's lyre was still to be gilded, but it was almost complete.

The model for the nude statue of Apollo, holding a lyre, had been Gracchus' 19 year old slave-boy, Petronius. As one of Gracchus' most handsome slaves, he was an ideal model for the most beautiful of all the Olympian gods.

As Gracchus stood and contemplated the magnificent statue, he said, quietly to himself, a prayer to the great god, patron god of the young Octavian, later known as the 'Divine Augustus', asking for the god's guidance in the difficult future that undoubtedly lay ahead.

Listen, the Holy One is near.

The rustling of cypresses announce him,

We sing to him our dark, resounding song,

We move around his white, pillared temple,

Look below where the cool streams run;

There all roam today in nakedness.

Blissfully they drink in the scents and sounds of the meadows,

And all gaze up into the blue heights.

And all rejoice, and all gather

This world's great blossoms of joy.

We, however, will bend down to take the fruit

that falls, golden, between dreaming and waking.

We bring it in silver bowls

To the temple, beside the spear and the shield.

Spread your fragrance, and shine forth

to the world this glorified image!

After having a little breakfast, Gracchus called for Terentius. Terentius arrived at Gracchus study looking understandably concerned.

"I was worried, Dominus," he began. "After you saw Novius, you locked yourself away, and I was concerned about what the old gentleman might have said to you."

"Well, Terentius, I needed time to think," Gracchus explained.

"And what did Novius have to say about the scroll, Dominus?" Terentius asked.

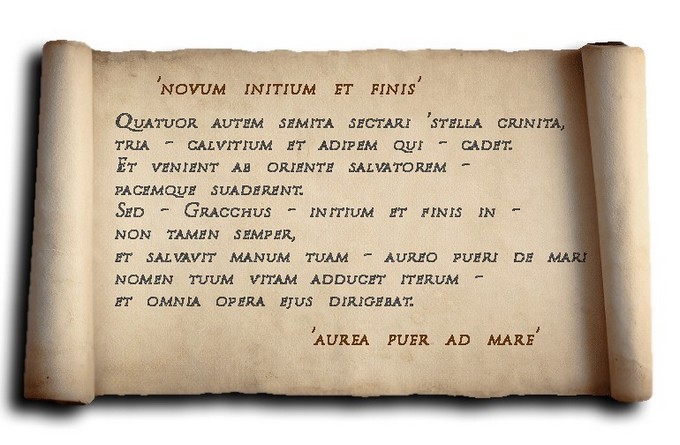

"Well, he agrees with us about Caesaris aster, but he says that it is meant to represent the desire to become Emperor and this is where the contents of the scroll become dangerous for anyone, including you, who becomes aware of the meaning of the oracle," Gracchus explained.

"I understand, Dominus. My lips are sealed," Terentius said, reassuring Gracchus.

"So it seems that there will be four individuals who will attempt, soon it seems, to become emperor, but only one will succeed and this will probably result in some kind of civil war," Gracchus continued wearily.

"Well, there's nothing we can do about that, except avoid getting involved," Terentius said, wondering where all this would lead.

"The most worrying thing that Novius said was that that he foresaw my demise some time after the political upheavals, and that's where the strangest part of the prophecy lies. It seems that the 'aurea puer ad mare' is our young Markos," Gracchus went on.

"But that's doesn't make sense!" Terentius exclaimed, "He's only a slave-boy! Why should he be included in a prophecy from the Sibyl?"

"Exactly!" Gracchus replied, "And that's what I said to Novius, but the prophecy seems quite clear and quite specific. From the way that I read it, it appears that after my demise he should take my name, and position, and carry on my work…" Gracchus continued to an incredulous Terentius.

"But that's absurd!" Terentius blurted out, forgetting for a moment his position as Gracchus freedman.

"Absurd it may seem," Gracchus replied, "But I knew from the beginning that there was something strange about the boy. His manner, his bearing, his speech. He was not a normal slave-boy. And what about that tale that Arion gave you, where the boy claimed to be the son of the Roman official killed by the pirates, and not the official's Greek slave-boy."

"Yes. But that's a story many slaves give, claiming to be freeborn," Terentius interjected.

"Yes, but they don't get a prophecy from an Olympian god to back up their claim!" Gracchus retorted.

There was silence in the room for a moment, as the implications of what Gracchus had just said became plain.

"I'm sorry, Dominus," Terentius then said, quietly. "I was forgetting myself. You are quite right. There is much more to this than appears on the surface, and you need to plan what you should do carefully. And I swear to you that I shall help and support you in every way that I can," Terentius continued.

"Thank you Terentius. I knew I could rely on you."

"So what shall we do?" Terentius asked.

"About the men who would be emperor, and the civil war? Nothing!" Gracchus replied. "The god has given us a timely warning, and it should enable us to avoid becoming involved. For our own safety we must say absolutely nothing about this. As for my demise, that is in the hands of the gods. As for Markos, that will need some thought." Gracchus continued. First you must go back to Arion, the slave trader, and question him thoroughly, but without letting him know the reasons for your questions. Say that your questions are prompted an inquiry from Rome. Meanwhile I must speak carefully to the boy today, and start making plans. And before you go to Arion, see that the statue of Apollo is gilded and finished immediately, and then have a second statue made, with young Petronius as the model. The original shall be dispatched as soon as possible to the temple at Cumae. And get the architect to design a shrine to Apollo in the main atrium, opposite the shrine to Hermes, and have him bring me the drawings as soon as possible."

"Of course, Dominus!" Terentius replied.

While Terentius started his long and arduous journey to Brundisium, Gracchus called for a messenger-boy to go and collect Markos. At the same time, he called for Quintus, as he wanted a record of his intended conversation with Markos. Quintus bustled into the room, with his cerae (wax tablets).

"Quintus, I want a record of my interview with this boy. When he enters the study, see that he is seated, as I want him to feel comfortable. In that way we may be more likely to get at the truth," Gracchus said, as he tidied his desk.

"Yes, Dominus!" Quintus replied, as he prepared a chair for Markos.

Markos, as usual in the morning, was at the main entrance to the villa with Glykon when the messenger-boy found him.

"Gracchus wants to see you!" the boy said breathlessly.

Glykon raided his eyebrows, wondering what was afoot, while Markos looked worried. Markos started to think about all the possible occasions, recently, when he may have said something untoward, that Gracchus might have taken exception to, especially regarding the trip to Cumae, but could think of nothing. Reluctantly, he followed the messenger-boy to Gracchus' study. As soon as he entered, Quintus offered him a chair. This was very odd, as slaves never normally sat in the presence of their master.

"Don't worry, Markos," Gracchus said reassuringly. "Sit down. I want you to be comfortable for our little chat."

Markos sat, by now very worried at this strange turn of events. Meanwhile, Quintus settled himself in a corner, with his stylus hovering over his wax tablet.

"Thank you, Dominus!" Markos said nervously.

Markos noticed that Gracchus looked very tired.

"You have been here some considerable time, Markos, and I have been very pleased with your work, and your attitude towards your studies and your training," Gracchus began.

"I have given you privileges, and special treatment because you are obviously intelligent, but also already well educated. Some have suggested that you are too well educated for an average slave, so there lingers in my mind the question of who you really are. Well?" Gracchus leaned back, leaving the question hanging in the air.

"You know who I am." Dominus, Markos said unsteadily. "Arion, the slave dealer explained that to Terentius."

"Yes, but even Arion was unsure of his facts," Gracchus retorted.

Markos was by then panicking. "But Dominus, if I say anything else, I may find myself being beaten, or something even worse!"

"If you tell me the truth, then no harm will come to you," Gracchus said, reassuringly.

Markos began very quietly, and haltingly, frightened that at any moment Gracchus would loose his temper.

"My father was Gaius Agrippa Aelius, and my name, before I was captured, was Marcus Gaius Aelius," Markos said slowly and with difficulty.

"I was born in Athens. I never met any of my parent's family, and have no idea who they are. My father saw that I was well educated, but I had problems with both my parents, and spent most of my time with my father's Greek slaves, and other Greek friends, which is why I have a Greek accent. When my parents were killed, I deeply regretted being a bad son, and so as not to disgrace them any further, I allowed people to think I was my parents' Greek slave-boy. Now I am happy here in your 'domus'. The pirates could have killed me, but instead they allowed me a new chance in life, and although I am now a slave, I consider that Tyche has been kind to me."

Tyche (Τύχη) meaning 'luck'; Roman equivalent: Fortuna, was the presiding deity that governed fortune and prosperity. She is the daughter of Aphrodite and Zeus or Hermes. In literature, she might be given various genealogies, as a daughter of Hermes and Aphrodite, or considered as one of the Oceanids, daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, or of Zeus. She was connected with Nemesis and Agathos Daimon ('good spirit'). The Greek historian Polybius believed that when no cause can be discovered to events, then the cause of these events may be fairly attributed to Tyche. The constellation of Virgo is sometimes identified as the heavenly figure of Tyche, as well as the goddesses Demeter.

As Markos finished, he hung his head, as if ashamed, and there was a palpable silence in Gracchus' study.

"If you wish to beat me now, or do worse, then do so, if you think I have lied, but I swear to you that I have told you the truth," Markos finally said.

"Leave us!" Gracchus said quietly to Quintus, "And say nothing of this to anyone!"

Quintus, obviously confused by what had transpire, left the room.

Gracchus was staring at Markos.

"Well, young Marcus, it looks like Terentius has made an unnecessary journey. I sent him to speak to Arion, but I hardly think that is needed now," Gracchus smiled, but Markos (or was it Marcus?) didn't realize, because he was still sitting shamefully, with his eyes lowered.

"So, young man, what are we to do with you?"

"I do not know, Dominus," Markos mumbled.

"For the moment, Marcus, nothing will change. You will continue to be the slave-boy Markos, but I intend to give you further training in the work of my freedmen, such as Terentius," Gracchus said, and Markos nodded in acknowledgement.

"You will say nothing about our conversation, nothing about your parents, and nothing about your time in Athens," Gracchus continued. "I will only say this to you, in confidence. It has been given to me that the gods, and one in particular, favor you, and that there is a great future for you, if you can be patient. Study hard, learn, and wait."

Gracchus sat back, waiting for a response, but there was none.

Markos was simply too confused by all the many things that had happened to him recently to take in, fully, what Gracchus was saying to him.

Gracchus of course understood.

"Just take your time, my boy, and think about what I have been saying, and if you have any quetions, or need any help, just speak to Terentius… You may go!"

"Thank you, Dominus!" Markos replied, quietly, and with that he left Gracchus' study, bewildered, but somewhat relieved.

'Favoured by the Gods', the phrase kept ringing in his ears.

Which God, and why, and what would come of it…

But what Markos didn't realize was that, on that morning, the first rays lighting the dawning of his eventual freedom had began the illuminate an otherwise dark sky.

and the story continues – Gracchus, as a result of the prophecy from Apollo – decided to train Markos further, and introduces him to the world of the arena and gladiators.

XIV. De Spectaculis

14. Spectacles

This chapter forms the prelude to Chapter XV 'Dies Ludorum' ('The Day of the Games', Markos' first visit to a Roman Ludi)), and gives much detailed and useful information about Roman amphitheatres, and the nature of Gracchus' involvement in the Games.

While we often talk about 'amphitheatres' and 'arenas' (arena is actually Latin for sand, harenam), such structures were also often known by the older term, Spectacula (from which we derive the word 'spectacular').

Skip the introduction

An amphitheatre, also known as a spectacula, is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ἀμφιθέατρον (amphitheatron), from ἀμφί (amphi), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and θέατρον (théātron), meaning 'place for viewing'.

Ancient Roman amphitheatres were oval or circular in plan, with seating tiers that surrounded the central performance area, like a modern open-air stadium. In contrast both ancient Greek and ancient Roman theatres were built in a semicircle, with tiered seating rising on one side of the performance area. Ancient Roman amphitheatres were major public venues, circular or oval in plan, with perimeter seating tiers. They were used for events such as Ludi, including gladiator combats, venationes (animal hunts) and executions, and also, in Hellenised areas, and under Hellenised Emperors (Nero, Hadrian etc) for Hellenic Games (gymnastics, athletics. wrestling and boxing) and also for theatrical performances (see below), and re-enactments of mythological dramas (see Sporus Chapter XI). Genuine munera were no longer celebrated in amphitheaters, and were only rarely performed during the empire in private venues (see munera ad Augustum). About 230 Roman amphitheatres have been found across the area of the Roman Empire. Their typical shape, functions and name distinguish them from Roman theatres, which are more or less semicircular in shape; from the circuses (akin to hippodromes) whose much longer circuits were designed mainly for horse or chariot racing events; and from the smaller stadia, which were primarily designed for athletics and footraces. The earliest Roman amphitheatres date from the middle of the first century BC, but most were built under Imperial rule, from the Augustan period (27 BC-14 AD) onward.

A Roman amphitheatre is normally made up of three main parts; the cavea, the arena, and the vomitorium. The seating area is referred to as the cavea (Latin for enclosure). 'Cavea' is formed of concentric rows of stands which are either supported by arches built into the framework of the building. The cavea is traditionally organised in three horizontal sections, corresponding to the social class of the spectators: The ima cavea is the lowest part of the cavea and the one directly surrounding the arena. It was usually reserved for the upper echelons of society. The media cavea directly follows the ima cavea and was open to the general public, though mostly reserved for men. The summa cavea is the highest section and was usually open to women and children (this section was not included in Gracchus' private arena in Baiae). The front row was called the prima cavea and the last row was called the cavea ultima. The cavea was further divided vertically into cunei. A cuneus (Latin for wedge; plural, cunei) was a wedge-shaped division separated by the scalae, or stairways. The arched entrances both at the arena level and within the cavea are called the vomitoria (Latin 'to spew forth'; singular, vomitorium) and were designed to allow rapid dispersal of spectators.

***

Gracchus' hobby was the Ludi, the 'Games'. This was not at all unusual for a Roman male, although it was not entirely in keeping with his love of all things Greek. Gracchus, however, was even more unusual, in that he could afford to indulge his hobby in ways that others could only dream of. Gracchus not only had his own 'stable' of handsome young gladiators, wrestlers, boxers and others, but, in addition, he had built for himself his own amphitheatre in the town of Baiae, close to his villa.

When the word amphitheatre is mentioned, people almost always think of the Colosseum, (more correctly known as the 'Flavian Amphitheatre', in Rome). That amphitheatre, however was unique, as regards its size and its facilities, and would not be completed until AD 80.

The 'Colosseum' or 'Coliseum', also known as the Flavian Amphitheatre (Latin: Amphitheatrum Flavium), is an oval amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome. Built of mainly of concrete, it is the largest amphitheatre ever built and is considered one of the greatest works of architecture and engineering ever. The Colosseum is situated just east of the Roman Forum. Construction began under the emperor Vespasian in 72 AD, and was completed in 80 AD by Titus.

There were two other amphitheatres near Baiae. One was was situated at Cumae, and one at Pompeii. The amphitheatre at Pompeii was was the first amphitheatre to be built of stone, in 80 BC, built with the private funds of Quinctius Valgus and Marcius Porcius, (before amphitheatres had been built of wood, or munera and ludi had taken place in fora, and other large public spaces.) The amphitheatre at Pompeii was subsequently buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, that also buried Pompeii itself and the neighbouring town of Herculaneum, (Gracchus' amphitheatre at Baiae, however, survived). The amphitheatre at Cumae was very small, and also of very early construction.

But back to our story… Gracchus charged spectators for the public ludi (Games) that he staged in his amphitheatre, but this was not a significant source of income for him. (Gracchus' main sources of income were from the buying, selling and leasing of slaves, the importation of Greek paintings and sculptures, the production of 'opus caementicium', and the agricultural produce derived from his vast estates in Latium, Campania and Achaea (Αχαΐα).

Gracchus, of course, took no direct part in these commercial activities, as it was considered unworthy and dishonourable for a patrician to indulge in 'trade', and so it was Gracchus' freedmen who were actually responsible for Gracchus' fabulous wealth.

At the time that Gracchus introduced Markos to his amphitheatre, the amphitheatre at Pompeii was inoperative because of a ten year ban, imposed by the Roman authorities, as a result of serious rioting by supporters of opposing teams of gladiators.

It was the day after Gracchus' interview with Markos. Gracchus, himself, was feeling rather at a loss, as his 'right-hand man', Terentius was on a 'fool's errand' to Brundisium, and would not be back for some days. Gracchus felt that he now had to involve his young protege, Markos, in more aspects of his life, and so he decided to take Markos to his amphitheatre, to introduce him to the world of the ludi, and its entertainments.

Interlude, Historical Evidence for the Roman Games

Skip the interlude

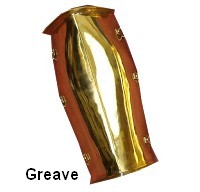

There were, we are led to believe, many types of gladiators, but the various classifications are only suggestions, as a wide diversity of evidence survives, from many periods, and over a wide geographical area. Different types of gladiators with different names there certainly were, but how exactly each one was equipped, what particular role they took in the fighting, and how that differed over the centuries of gladiatorial display throughout the whole expanse of the Roman empire is very hard indeed to judge. The question becomes even more tantalizing when we try to fit into the picture the authentic items of gladiatorial armour that still survive, splendid helmets, shields, protections for shoulders and legs (or perhaps arms: it is not always clear exactly which part of the body the makers had in mind). There is a considerable quantity of this, most of it, about 80 per cent, from the gladiatorial barracks at Pompeii, (see above) excavated in the eighteenth century. At first sight, even if it is not from the Colosseum itself, this material provides precious direct evidence of what an ancient combatant in that arena would have worn, only a few years before the Colosseum's inauguration. In addition, it matches up reasonably well with some of the surviving ancient images of gladiators. Yet it is far too good to be true, quite literally. Most of the helmets are lavishly decorated, with embossed with figures of barbarians paying homage to the goddess 'Roma' (the personification of the city), of the mythical strongman Hercules, and with a variety of other more or obviously appropriate scenes. It perhaps fits well with Martial's emphasis on the arena's sophisticated play with stories from classical mythology that one of these helmets is decorated with figures of the Muses. It is also extremely heavy.

The average weight of the helmets is about 4-5 kilos [9-11 pounds], which is about twice that of a standard Roman soldier's helmet, and the heaviest of these 'gladiatorial' helmets weighs in at an almost ridiculous 7 kilos [15 pounds]! The average weight of the helmets is about 4-5 kilos [9-11 pounds], which is about twice that of a standard Roman soldier's helmet, and the heaviest of these 'gladiatorial' helmets weighs in at an almost ridiculous 7 kilos [15 pounds]!

Add to this the fact that none of these items of armour them seem to show any sign of wear and tear, no nasty bash where a sword or a trident came down fiercely, no dent where the shield rolled off and hit the ground. It is hard to resist the suspicion that these magnificent objects were not actually gladiatorial equipment, in regular use. Some archaeologists, predictably have tried very hard to resist that suspicion, and have resorted to some desperate arguments in the process. 'Maybe this Pompeian armour was a new consignment, not yet knocked around in the arena. Maybe the short length of the gladiatorial bouts meant that such weight of equipment was manageable for these fit men; it was not, after all, like fighting a day, long legionary battle. Maybe, and this is where desperation passes the bounds of plausibility- the helmets were known to be so strong that no canny opponent would have bothered to take aim at them, hence their apparently pristine state.' Maybe, but much more likely, is that this armour was the display collection, 'parade armour', used only when the gladiators paraded into the arena at the start of the show (to be replaced by more practical equipment as soon as the fighting started), or on other ceremonial occasions. It was the also the kind of equipment that would best symbolize the gladiator on funeral images or other works of art.

The programme of the ludi

And what of the standard programme of displays in the amphitheater: animal hunts in the morning, executions at midday, gladiators in the afternoon (with the public gladiatorial dinner the evening before to allow the punters to study form)? lt is quite true that each of these elements is referred to by ancient writers describing the shows. The question is whether or not it is right to stitch all these references together into a 'programme'. This is a trap modern students of Roman culture often fall into: pick up one reference in a letter written in the first century AD, combine it with a casual aside in a historian writing a hundred years later, a joke by a Roman satirist which seems to be referring to the same phenomenon, plus a head-on attack composed by a Christian propagandist in North Africa; add it all together and, you've made a 'picture', and supposedly 'reconstructed' an institution of ancient Rome. It is exactly this kind of historical procedure which lies behind modern views of what happened at a Roman baths, or at the races in the Circus Maximus, or at almost any Roman religious ritual you care to name. And it lies behind most attempts to reconstruct the shows in the amphitheater too.

Why is it usually assumed that the lunch interlude was the time for executions? Because the philosopher Seneca writing in the mid first century AD, before the Colosseum was built, in a letter concerned with the moral dangers of crowds, complains that the midday spectacles in some shows he had attended were even worse than the morning. 'In the morning men were thrown to lions and bears, at noon to the audience' he quips. And he goes on to deplore the unadulterated cruelty, while explaining that its victims are criminals, robbers and murderers.

That is the only evidence for the 'lunchtime executions'. In fact, there is just as much evidence for some kind of burlesque, or comedy interlude at lunchtime. And that may have been what Seneca was expecting, when he writes that he was hoping for some 'wit and humor'. Why is it believed that gladiators regularly had a public meal the night before their show? Because the unreliable Christian writer, Tertullian, rather puzzlingly, claims that he himself does not recline in public 'like beast fighters taking their last meal'. There is certainly no evidence at all for the punters coming along to study form; in fact, we have no direct evidence at all for widespread betting on the results of this fighting. That is an idea that comes mostly from the imagination of modern historians, trying to make sense of the shows by assimilating them to horse racing, or to ancient chariot racing, which certainly did attract gambling. Perhaps most surprising of all, considering all the depictions of gladiators in the contemporary media, is the fact that it appears that there is only one account of a specific gladiatorial bout to survive from the ancient world. We have plenty of boastful claims of gladiatorial numbers, a good deal of discussion about the appeal of the gladiators themselves and the valor of the fighting, and countless very imaginative, and probably inaccurate images of these distinctively dressed combatants, decorating everything from cheap oil lamps to mosaic floors (mainly in the distant provinces). Yet the only thing approaching a description of an actual contest between two individual gladiators is the ancient equivalent of a 'goalless draw' in the Colosseum, in AD 8o. That is the only evidence for the 'lunchtime executions'. In fact, there is just as much evidence for some kind of burlesque, or comedy interlude at lunchtime. And that may have been what Seneca was expecting, when he writes that he was hoping for some 'wit and humor'. Why is it believed that gladiators regularly had a public meal the night before their show? Because the unreliable Christian writer, Tertullian, rather puzzlingly, claims that he himself does not recline in public 'like beast fighters taking their last meal'. There is certainly no evidence at all for the punters coming along to study form; in fact, we have no direct evidence at all for widespread betting on the results of this fighting. That is an idea that comes mostly from the imagination of modern historians, trying to make sense of the shows by assimilating them to horse racing, or to ancient chariot racing, which certainly did attract gambling. Perhaps most surprising of all, considering all the depictions of gladiators in the contemporary media, is the fact that it appears that there is only one account of a specific gladiatorial bout to survive from the ancient world. We have plenty of boastful claims of gladiatorial numbers, a good deal of discussion about the appeal of the gladiators themselves and the valor of the fighting, and countless very imaginative, and probably inaccurate images of these distinctively dressed combatants, decorating everything from cheap oil lamps to mosaic floors (mainly in the distant provinces). Yet the only thing approaching a description of an actual contest between two individual gladiators is the ancient equivalent of a 'goalless draw' in the Colosseum, in AD 8o.

So, what the spectator would actually have seen in any amphitheatre was probably much less like the figure invented by Gérome (who almost certainly had seen the Pompeian finds), and much more like the more lightly clad, though still recognizably 'gladiatorial', gladiators envisaged in 'The Roman Principate' blog, and similar to the rather more 'nifty' fighters depicted in the casual graffiti from Pompeii.

***

Once again, back to our story…

For Gracchus, it was important to have Markos involved in the running of the amphitheatre in Baiae.

Because of Novius' interpretation of the oracle of Apollo, Gracchus had come to believe that his time was 'limited' and that 'death' ('Thanatos) was 'stalking' him, and that Apollo had chosen Markos to continue much of Gracchus' 'work' and part of that work, probably the simplest and easiest, was the running of the Amphiteatre and Ludus in Baiae.

In Greek mythology, Θάνατος, Thanatos, (Death, from θνῄσκω thnēskō 'to die') was the daemon personification of death. He was a minor figure in Greek mythology, often referred to, but rarely appearing in person. His name is transliterated in Latin as Thanatus, but his equivalent in Roman mythology is Mors. The Greek poet Hesiod established in his 'Theogony' that Thánatos is a son of Nyx (Night) and Erebos (Darkness) and twin of Hypnos (Sleep).

"And there the children of dark Night have their dwellings, Sleep and Death, awful gods. The glowing Sun never looks upon them with his beams, neither as he goes up into heaven, nor as he comes down from heaven. And the former of them roams peacefully over the earth and the sea's broad back, and is kindly to men; but the other has a heart of iron, and his spirit within him is pitiless as bronze: whomsoever of men he has once seized he holds fast."

In Roman times, Thanatos came to be seen as a beautiful 'Ephebe' (young teenage boy). He became associated more with a gentle passing than a woeful demise. Many Roman sarcophagi depict him as a winged boy, very much akin to Cupid. He is often depicted dressed in black and carrying a sword. Also in Roman times, he letter θ, the first letter of Thanatos' name, was written on arena score cards, to indicate which individuals had been killed in the arena

Markos, however, was only 16 years old (although the boy was not exactly sure of his age), and while well educated, and speaking both Greek and Latin, he had little practical experience of the adult world. Having been brought up in Athens, he had little or no experience of the Roman ludi, having been involved in the typically Hellenistic 'Gymnasion' (generally, the Greeks, particularly in Athens, were no lovers of the Roman Gladiatorial Ludi, despite the fact that it had its origins with the Greek influenced Etruscans).

So Gracchus decided to take Markos to his amphitheatre in Baiae.

Gracchus remembered the words that Markos had spoken the previous morning, "Now I am happy here in your 'domus'," and therefore he was no longer concerned that Markos would try to run away.

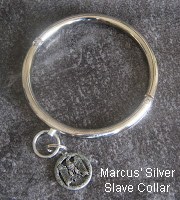

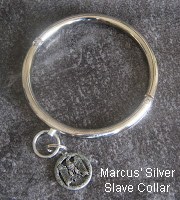

Gracchus therefore took the unprecedented step of informing Vulcan, (the blacksmith and metal worker we met in Chapter III), that Markos should be fitted with a silver slave-collar with an unobtrusive 'catch', so that it could be removed when necessary. Gracchus therefore took the unprecedented step of informing Vulcan, (the blacksmith and metal worker we met in Chapter III), that Markos should be fitted with a silver slave-collar with an unobtrusive 'catch', so that it could be removed when necessary.

Vulcan appeared to be shocked, and also puzzled, as he had never been asked before to make such a collar, but lacking the ability to speak, he was unable to communicate his concern to Gracchus.

Gracchus, however, was obviously aware of Vulcan's feelings, and was prepared to make an explanation, knowing that Vulcan would be unable to tell anyone else.

"It's difficult to explain, Vulcan, but the gods have demanded that this boy is given special treatment.

Sometimes he is to appear as 'freeborn', and sometimes as a slave.

The gods promise that he will be faithful, and not leave us, so he may be trusted.

So I need you to help to perform the will of the gods.

But this is our secret."

Vulcan nodded and bowed.

He was a simple soul, although a superb craftsman, and Gracchus knew that an appeal to the authority of the gods would ensure his co-operation.

And so Vulcan got to work with a will.

Gracchus wanted the people running the amphitheatre, who normally had little or no contact with Gracchus' villa in Baiae, to think of Markos (because he did not wear a collar) as 'freeborn', (which Gracchus now believed to be the actual fact). In that way the boy would receive more respect, a respect which Gracchus wanted Markos to grow to accept, and eventually expect.

Markos, therefore, was very surprised when a messenger-boy knocked on his door, waking him up early, and then took him down to Vulcan's workshop, to have his new slave-collar fitted. It was identical to his previous collar, so no one would notice the change, but now Markos could take it off when Gracchus required him to appear 'freeborn', and Markos could also take it off to sleep, as he often found it uncomfortable to wear in bed.

On his return to his room, after having the collar fitted, he was equally surprised to find that a fine new tunic had been left on his bed. There then followed another knock on the door, and another messenger boy informed Markos that he was to get dressed, (and wear the bracelets, that Gracchus had given him for the convivium), and report to Gracchus at the main entrance.

Gracchus, who was talking to another of his freedmen, was waiting for him, and curtly told Markos to go and wait in the carriage, which was parked in the driveway. Markos got into the carriage, and sat nervously waiting.

When Gracchus joined Markos, the carriage immediately started on its short journey to the amphitheatre.

"So Marcus," Gracchus began, using the Latin form of Markos' name. "You are looking very smart in your new tunic."

"Thank you, Dominus." Marcus respectfully replied.

"Today we are going to my amphitheatre. As for as my people there, as far as they are concerned you are my 'nephew', and will refer to me as 'uncle'. So now you may take off your slave-collar, and I will look after it for you until we return to the villa."

Gracchus mentioned the slave collar with a gleam in his eye, as if it were some 'naughty' secret that only he and Markos were sharing.

"As for my people at the arena, Petronius you have met before, but he is trusted, and will be discreet. One other boy, Atticus, you will have seen before, he fought in the munera, during the convivium. He will, however, be fighting today, and he will not be leaving the arena alive."

Markos had no choice but to agree to Gracchus subterfuge, but he was surprised and rather shocked that Gracchus seemed to certain of the outcome of Atticus' fight in the arena.

It was only a few minutes until the fast moving carriage enter the town of Baiae, and stopped outside Gracchus' amphitheatre.

Now most readers, when the term amphitheatre is used, will automatically think of the Amphitheatrum Flavium, usually referred to, inaccurately, as the 'Colosseum'. At the time of our story, however, nothing like the 'Colosseum' had ever been built, despite the fact that it appears, anachronistically, in numerous films (Quo Vadis, Demetrius and the Gladiators, etc. etc.). The original film, Spartacus (1960), did accurately use a small amphitheatre, but was inaccurate as amphitheatres, in the time of the republic, were temporary structures, built entirely of wood, and not stone. (It is also believed that gladiators did not wear sandals or footwear, bare feet had a better grip on the sand.)

The nearest the mass media has ever got to a realistic image of a gladiatorial setting (in a public fora, although the fight was inaccurate) was in the TV mini series, Rome, and, of course, it was a lot cheaper for the production company than building even a wooden amphitheatre, as was used at the time. (There is a problem, again however, with the sandals)

Gracchus' amphitheatre was unusual, in that it was built entirely of concrete, faced with Travertine stone, and other marbles. Compared to the monstrous Amphitheatrum Flavium (only built much later, and where only the spectators in the most privileged areas could actually see in any detail the events on the sand), Gracchus' arena was small, and compact, giving all the spectators a excellent view. It was mainly patronized by the wealthy visitors to the 'beach resort' of Baiae, and those who owned lavish holiday villas in the area.

A fee was charged for entry to the amphitheatre in order to view Gracchus' entertainments. In providing his entertainments, Gracchus was not aiming at providing panem et circenses. Such diversions were distractions, or the mere satisfaction of the immediate, shallow requirements of a populace, and were offered as a 'palliative', by either the Roman State or aspiring politicians, and had been described by Juvenal as 'bread and circuses (games)'.

Decimus Iūnius Iuvenālis (right), known in English as Juvenal, was a Roman poet active in the late 1st and early 2nd century CE, author of the Satires. (Note, however, that Juvenal lived after this story, and therefore his mention is somewhat anachronistic).

Gracchus, however, had no interest in, or need to curry favour with the plebs (the poor and mainly unemployed), politicking was not his 'game', and he wanted a sophisticated and appreciative audience for his 'shows'. As we have said, the arena was Gracchus' personal indulgence, his 'hobby'. The entertainments that Gracchus enjoyed providing were not restricted to 'Ludum gladiatorium' (gladiatorial games), however, but in keeping with his 'pan-Hellenism', also on occasions consisted of drama and comedy, ludi scaenici, (including 'mime').

Roman plays were presented in the daytime, sometimes before, sometimes after, the noon meal. The average comedy was about two hours long. The characters wore Greek dress. Wigs were employed, a grey wig for an old man, black for a young man, and red for a slave. For the greater part of Roman history the profession of acting was confined to men, the women's parts being taken by youths. There was no limit to the number of actors. Division into acts or scenes was made only when the actor left the stage to prepare for the next appearance. During such intermission a flute player entertained the audience. In both comedies and tragedies probably some of the dialogue was sung, as in modern opera.

Roman mimes. The most popular of the stage entertainments were the mimes, short scenes given by two or three actors, with spoken dialogue. In these skits the actor impersonated rustics, sight-seeing provincials, pompous officials, and other decent but dull types. Of course such a figure, once connected with the ancient dignity of the patricians, could easily be converted into burlesque. The dialogue of the mimes was in verse. The wealthy, as at Baiae, as well as the lower classes delighted in mimes.

Pantomimes, the Roman word does not have the same meaning as it has today. The shows, usually given by a single male dancer, were of three kinds: simple mimicry without music or words, but with dancing; secondly, mimicry with instrumental music; and thirdly, mimicry with music and words, the latter frequently given to a chorus. Some of the pantomimes were modifications of the Atellan fables and Satyr plays. Often they reproduced tales of which were (by modern standards) sexually explicit, illustrated fully and unmistakably, by exaggerated gestures, and displaying various passions and emotions. Cymbals, gongs, castanets, rattles and drums were used. The dancers appearing in pantomimes were much admired for their outstanding beauty.

Actors were never recognized as skilled professionals, and were considered infamia, as with gladiators and professional athletes who appeared naked in public. Performers of lower class, (including slaves), danced, often naked and in a sexually explicit manner, and the wealthy patrician class was happy to be entertained, while supposedly disproving.

The day was hot, with brilliant sunshine, the street was busy, and groups of 'well-heeled' patricians were gathering in anticipation of the amphitheatre opening. The entrance to Gracchus' arena rose up before them, as the carriage came to a halt. Young slaves quickly moved forward to open the carriage door, put in place a portable wooden step, and ensure that the crowded pavement was kept clear. Gracchus stepped out, and was followed immediately by Marcus.

As the slave-boys bowed respectfully, Gracchus and Marcus entered the main prothyrum (foyer), where Petronius, Gracchus' teenage slave (and the model for the statue of Apollo), was waiting for them, with his twinkling eyes and flashing smile, and Marcus was entranced.

and the story continues, Gracchus and Marcus spend the day at Gracchus' Amphitheatre in Baiae, where they witness the defeat and death of young Atticus, an 'arranged' death, designed to keep the secret of Marcus' freeborn status…

XV. Dies Ludorum

15. The Day of the Games

"Greetings, Dominus!" Petronius said with a broad smile. "We are honoured that you come to visit us!".

"Indeed, Petronius. And I am very pleased to see you!" Gracchus replied, taking the handsome young slave along with him, as he made his way to the editors' box.

The Editor was the title given to the individual who was financially responsible for the performances in the arena. Often the editor would be an aspiring politician or prominent public official. In Gracchus' amphitheatre the Editor was, by default, Gracchus, but often he was not present, and one of his freedmen would take his place.

"I see that you have brought your young nephew, Marcus, with you today," Petronius continued, with a conspiratorial smile to Marcus.

It was obvious that Gracchus had ensured that Petronius was well primed.

"I trust that he will enjoy the day's entertainment that you have prepared!"

"Well, in truth, Petronius, it's the 'entertainment' that you have prepared, and I'm sure he will enjou it," Gracchus replied.

Having reached the Editor's Box, Petronius ensured that Gracchus and Marcus had everything they required.

"Please excuse me, Dominus, but I now have to go and help with the arrangements! If you require anything just ask young Adonios," Petronius said, apologetically, leaving Marcus and Gracchus, with Gracchus' two bodyguards and Adonios, in the Editor's Box.

It seemed that the cute 13 year old slave-boy, Adonios, whom Markos had first met at the Munera for Augustus, had obviously been let in on Gracchus' little ploy with regard to Markos being (at least while he was at the amphitheatre), freeborn, as the blonde lad seemed totally un-surprised by Markos' new role, or that Petronius referred to Markos as Gracchus' 'nephew', Marcus (the Latin version of his name).

It was probably at this point that Marcus began to truly understand some of the advantages that great wealth and power could provide, for here he was, raised up above the crowd, most of whom were patricians, and occupying the best vantage point in the amphitheatre, with servants at his beck and call, wearing the finest clothes, and above all he was, at least for that day, free!

De Pompa

The Procession

The Games began with a fanfare, which was the signal for the beginning of the Pompa.

The Pompa signalled the start of the Games; a blend of Greek, Roman, and Etruscan elements. The procession consisted of the gladiators, wrestlers, boxers dancers and actors who may be appearing in the entertainments, along with musicians, palm-bearers, the trainers and coaches, and various other officials and personnel, such as a sign-bearer whose placard gave the crowd information about the events. The pompa circensis took very much the form of a triumphus, (triumph), which was originally a civil ceremony and religious rite, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory in the service of the state or, originally and traditionally, one who had successfully completed a foreign war. Some genuine triumphs included ludi (games), as fulfilment of the general's vow to a god or goddess, made before battle or during its heat, in return for their help in securing victory. During the Republic, such ludi were paid for by the triumphing general, and it was in this way the Pompa which opened the normal ludi became associated with aspects of the Roman triumphus.

Gracchus, being a firm believer in the mos maiorum, the 'customs of the ancestors', was not prepared to turn his Pompa into an 'imitation' triumphus, and therefore dispensed with some of the more exaggerated aspects of the Pompa which would be seen in ludi in Rome. For him, the Pompa was simply an opening presentation, to the audience, of those who were to take part in the day's entertainment, and he forbade any appearance of the Editor (on this day himself, as he was in attendance), or any of his freedmen in the procession.

Ludi Mane

The Morning Entertainments

The amphitheatre didn't open until quite late in the morning, so the morning's program was quite brief. It was to begin with some 'boy fights'. These were fairly 'light-hearted' affairs, with young lads showing off their sword and wrestling skills, but with no intention of inflicting any real damage on their opponents.

This was to be followed by a mythological 'mime', accompanied with music. The subject was to be one of Gracchus' favourites, the 'Rape of Ganymede'. (That mythological subject had been the cause of Marcus nervousness at the time of the convivium, mainly because Marcus had not, at that time, understood Gracchus' fascination with Greek mythology). Petronius, who was mainly responsible for this production, was particularly proud of his achievement, and the whole piece 'went off' without a hitch, even the goats!, as you will see, if your read on…

In Greek mythology, Γανυμήδης (Ganymede) is a divine hero whose homeland was Troy. He was the son of Tros of Dardania, from whose name 'Troy' was supposedly derived, and of Callirrhoe. His brothers were Ilus and Assaracus. In the myth, he is abducted by Zeus, in the form of an eagle, to serve as 'cup-bearer' in Olympus. Homer describes Ganymede as the most beautiful of mortals:

'Ganymedes was the loveliest born of the race of mortals, and therefore the gods caught him away to themselves, to be Zeus' wine-pourer, for the sake of his beauty, so he might be among the immortals.', Homer, Iliad, Book XX, lines 233-235

The myth was a model for the Greek social custom of paiderastía, the socially acceptable erotic relationship between a man and a boy. The Latin form of the name was Catamitus (and also 'Ganymedes'), from which the English word 'catamite' is derived. Ganymede was abducted by Zeus from Mount Ida, near Troy in Phrygia. Ganymede had been tending goats, (see above) a rustic or humble pursuit characteristic of a hero's boyhood before his privileged status is revealed. Zeus turned into an eagle to transport the youth to Mount Olympus. In Olympus, Zeus granted Ganymede eternal youth and immortality, and the office of 'cup-bearer' to the gods. Plato accounts for the pederastic aspect of the myth by attributing its origin to Crete, where the social custom of 'paiderastía' was supposed to have originated. Ganymede was sometimes describes as the 'Eros' of love and desire between men and boys. Plato calls him 'Himeros' (Sexual Desire).

Not surprisingly, Gracchus was very pleased with Petronius' efforts. A dancer, (a slave owned by Gracchus) called Paris, had taken the part of a surprisingly youthful, and very virile and 'erect' Zeus. He was suspended on two wires from a wooden gantry, which was constructed over part of the arena, and 'flown' in, wearing his magnificent eagle wings (overlaid with real gold leaf), and nothing else, apart from a gold laurel wreath (borrowed from Gracchus, on the understanding that it would be returned, undamaged.)

There then followed a somewhat explicit 'mime', accompanied by music, and a reading from Ovid's Metamorphoses, which culminated in the young slave-boy, playing the part of Ganymede, being vigorously buggered by the remarkably 'well endowed' king of the gods.

"Oh fuck! You're too big!" the young slave boy grunted, as 'Zeus' forced open the squirming boy's anus.

(Now whether this was intended 'dialogue' - which would be unusual for a mime, or the lad's natural reaction, was difficult to tell, but it undoubtedly added to the verisimilitude of the presentation being an actual 'rape'.)

In a matter of moments, however, the entire bulk of the superbly endowed older slave's huge ppenis had disappeared inside the young lad, who immediately responded by getting a good sized erection, accompanied by appreciative murmurs from the extremely discrete audience. As Zeus started thrusting, it was plain to see, however, that the boy had become a willing partner responding, not only with an erection, but also an ejaculation and noisy orgasm, much to the satisfaction of the audience, who were fascinated by the whole performance.

De Raptu

The Rape

Skip De Raptu and continue the story

Paris, playing the part of Zeus, managed to land deftly on the sand close to 'Ganymede' (played by young Felix). While Paris flicked a catch on his wings that removed the wires that had supported him in his 'flight', Felix mimed a suitable surprise and alarm at the sudden arrival of the 'god'. Paris, anticipating fucking cute little Felix for some considerable time, was already massively erect.

Throughout all the rehearsals for the performance, Petronius had never let Paris actually fuck the boy, although it was made clear that this would be, literally, the 'climax' of the performance. This was because Petronius wanted Paris to be extremely 'excited' when he finally had his opportunity to have sex with the boy, and because he wanted Felix to respond to Paris' exceptional 'size' and virility with a suitable reaction.

Having 'landed', Paris then gently grasped the boy, and sitting on the sand, drew the boy down so that the lad ended up sitting on Paris' huge, erect prick. As the massive 'member' entered the boy, young Felix groaned, finding it difficult, at first, to accommodate the enormous bulk. Once Paris had fully penetrated Felix, the pair of them leaned back, lying on the sand, and Paris started thrusting, as the audience applauded.

"Fuck me hard, and wank me!" Felix whispered to Paris, as his boy-prick stiffened.

Paris first caught hold of the young lad's ball-sack in his hand, and gentle rolled and caressed them the boy's balls, and then he grabbed hold of the lad's rigid 'tool' and started jerking-off the squirming boy. For some time the only sounds in the large arena, which was nearly full, were the moans of young Felix, as he took the repeated thrusts of Paris' huge cock. In addition to Felix's moans, there were the deeper grunts from Paris, as he repeatedly rammed his swollen prick into the naked lad's tight, hot butt-hole. Eventually the pair managed to 'cum' at the same time, with Paris obviously pumping his spunk into the groaning lad, while young Felix squirted his 'boy juice' over his own smooth belly. Having accomplished the 'rape' elegantly, the breathless pair stood, bowed to the audience and, naked, and hand in hand, left the arena, leaving the tethered goats looking somewhat bemused.

While the Rape in the arena may seem to the readers of this story to be nothing more that a piece of harmless, if rather explicit 'fun' (if we ignore the youth of the boy Felix), like most events in the arena, it did have a link back to the ancient Etruscan, ('ancient' even to the Romans of Gracchus' day), rites of the munera. Firstly, while we would consider the story enacted to be mythology, a legend, to most Romans it was 'religion'. Equally, as it was an act of the King of the Gods (Zeus, known to the Romans as 'Jupiter Optimus Maximus'), it was therefore a religious justification for 'pederastry', (love, infatuation and/or lust, often involving a sexual relationship, or copulation, between older and younger males., love of boys). In addition the penetration of the slave taking the part of Ganymede by the older male has connotations related to gladiatorial combat, and therefore the munera, in that the penis was commonly referred to, in slang terms as the gladius, and therefore the boy was being 'penetrated' with a gladius. While it is commonly now believed erroneously (as a result of the 'mass media') that the Roman Games (ludi) was just one long succession of mindless killing, in actuality, many of the presentations were of drama, mime, ballet, and accompanied singing, but almost all these features made reference, in some way to the original ethos of the original, Etruscan munera.

***

Markos, while enjoying the artistry and ingenuity which Petronius had displayed in mounting the remarkable episode, was a little un-nerved when he considered the subject of the 'mime'. He recalled that Gracchus had referred to the myth of Ganymede during the interview, when Gracchus had told Markos that he was to be 'cup-bearer' at the convivium. He had thought that the matter had been put to one side, but now, at this special visit to the amphitheatre, the legend of Ganymede had appeared once again, and on this occasion in a quite explicit form.

However, Marcus' mind was put at rest early on, when Gracchus spoke to him, while the arena scenery was being reset.

"Well Marcus, my boy!" Gracchus said, smiling and turning to Marcus. "I think Petronius staged that extremely well, don't you? And even the goats behaved themselves!…"

Interlude, mythological re-enactments in the amphitheatre

Skip the interlude and continue the story

Mythological re-enactments were more in keeping with the Roman theatre than gladiatorial contests, and for the Romans were a no less important and distinctive a genre of displays in the amphitheatre. The contemporary media often portrays the program of the amphitheatre as one long succession of bloody (and often rather grubby) fights between gladiators. This was definitely not the case. Arena displays were varied (athletics, drama, dance and singing), and not grubby, but usually opulent and magnificent, (which is what those attending expected). While we have only one description of a gladiatorial fight in the whole of Roman literature, (in which both gladiators are supposed to have won! a draw, in other words), there are countless descriptions of 'theatrical' style performances (often, however, deadly, or sexually explicit), which often merged with the numerous tortures and executions. It should also be noted (in the light of the dearth of accounts of actual gladiatorial fights), that the numbers of gladiators reported to have fought in Roman arenas (mainly the Flavian Amphitheater in Rome), are almost certainly wild exaggerations, designed to boost the reputations of the consuls/emperors reported as staging the Games.

- Pasiphae, Martial recounts the re-enactment of Pasiphae, the wife of King Minos, and mother of the Minotaur. According to myth, it was King Minos who brought doom upon Pasiphae, cheating Poseidon of a magnificent bull that was meant to be sacrificed to him in return for legitimizing King Minos' claim for the throne. In punishment for this crime, Pasiphae was cursed to fall in love with the bull. Full of desire for the animal, she requested the craftsman Daedalus to construct for her a wooden cow covered in a hide so she could climb inside and join with the bull in his field. Ovid makes fun of the situation within his work, Ars Amatoria ('The Art of Love'), stating, "Pasiphae shouted for joy when the animal made her his mistress… Well, the lord of the harem, deceived by a wooden plush-covered dummy, got Pasiphae pregnant. The child looked just like his father." Martial's poem appears to show that this event was acted out before the audience in the amphitheatre. There is other evidence for dramatic executions of criminals in the Roman arena along these lines, (presumably the woman would not have survived the encounter, which we may assume to have been some form of quasi-judicial punishment).

A somewhat more easily staged alternative was to present a fight between Theseus and the Minotaur, (with the Minotaur obviously losing), in the arena.

- Dirce, In the legend, Dirce is tied to the horns of a wild bull, and dragged to her death by Zethus and Amphion, sons of Antiope, who were held prisoner by Dirce. In this case, the myth and re-enactment were essentially the same. Within the arena, a condemned woman, would be forced to re-enact this myth, and tied to the horns of a bull and dragged to her death.

- Prometheus, Later in the book, Martial focuses on the crucifixion of a man, who acted out the punishment of a legendary Roman bandit called Laureolus, until he was finally killed by a wild bear. According to Martial, this criminal simultaneously reminded the audience of the myth of 'Prometheus', whose particular divine punishment was to have his liver continually devoured by vultures during the day and grow back again at night. This is also an aspect of games that other writers pick out when they remark that criminals in the amphitheatre take on the mythological roles of Attis (who castrated himself), or Hercules (burned alive).

- Orpheus, Orpheus was another easily identifiable figure in mythology, and Martial describes a manipulation of the myth. Although Orpheus would have remained identifiable by carrying a lyre, perhaps even playing music and singing, the outcome of the myth was altered. Unlike the myth, Martial records that the death of 'Orpheus' was caused by a bear rather than the Bacchae.In this re-enactment, the mechanics of the amphitheatre would have been put into effect, taking advantage of the multiple entrances, trap doors, and scenic displays. 'Orpheus' would have entered the area with his lyre, while tame and harmless animals would have been slowly released. Some of these animals may have even been trained to interact with the character and his music. Finally, a bear, or some other ferocious animal, would have been released. Once the animal had been released, the individual playing 'Orpheus' would have been killed.Ironically 'Orpheus' would have been killed by the very beast he was meant to charm.

- Apuleius, Even closer to Martial's 'woman and the bull' is an episode in Apuleius' brilliant novel The Golden Ass. Apuleius recounts how a woman convicted of murder was condemned, before being executed, to have sexual intercourse in the local amphitheatre with an ass, in fact the human hero of the story, transformed into an ass by a magical accident. The brainy ass is not convinced that the lion (which is intended to kill the woman) will 'know' the script, and fears that it might well eat him instead of the woman, so he escapes before the performance. While it is possible that a bull may have been trained to have intercourse with a woman, the 'bull' may well have been a man in a bull costume, and that the 'reality' of the union was simply a public rape, performed in the arena.

- Attis, According to Ovid, Attis was a handsome Phrygian boy who was loved by the mother of the gods, Cybele.Attis consecrated himself to her by swearing eternal faithfulness, but subsequently betrayed her with a tree-nymph named Sagaritis. Attis was then driven mad resulting in his self-inflicted emasculation. Within Catullus' song 63, Attis is also described as a boy who emasculated himself as the result of the insanity Cybele infused on him. The end result was the same within the re-enactments. The individual who was to die as "Attis" would inevitably be castrated, which was may even have been self-inflicted. In order for "Attis" to actually castrate himself, it is likely that the individual would have been threatened with death if he refused to do so. It is also probable is that "Attis" would have been anally impaled, and instructed to castrate himself if he was to be freed.

- Persephone, A famous, but unsuccessful attempt at an arena re-enactment of a mythological story relates to the Rape of Persephone. Persephone (also known as Kore) was the daughter of Demeter, the goddess of the harvest, and Zeus. Persephone was abducted and raped by Hades. When Persephone was gathering flowers, she was entranced by a narcissus flower planted by Gaia (to lure her to the Underworld as a favour to Hades), and when she picked it the earth suddenly opened up. Hades, appearing in a golden chariot, seduced and carried Persephone into the underworld. In the year 69, the young, castrated catamite, Sporus became involved with the Emperor Vitellius. Vitellius planned for Sporus to play the title role in the 'Rape of Persephone' for the viewing enjoyment of the crowds, during a ludi. Sporus then committed suicide, to avoid being raped in public.

- Icarus, During the period of our story, there was a portrayal staged by the Emperor (Nero) of the story of Daedalus and Icarus. In this reconstruction, a young slave-boy took the part of Icarus and was 'flown' across the arena on wires, and then dropped from a great height, to his death onto the arena floor.

De Morte Attici

The Death of Atticus

After the 'Rape of Ganymede' there was some Greek style boxing, which had very little appeal for Gracchus.

He therefore took the opportunity to retire from the Editors' Box, and lounge on a couch to be served refreshments by Adonios.

Marcus stood to one side, feeling very awkward.

It was a strict rule that slaves always stood in the presence of their masters so, for Marcus, the situation was fraught with difficulty.

After a few moments Gracchus noticed that Marcus was standing.

"Marcus!" Gracchus exclaimed.

"Here you are not a slave, so take a couch and relax!"

Adonios was grinning, seeing at how awkward Marcus looked, but Adonios was remarkably good hearted, and quickly went over to Marcus and offered him refreshments.

"Now we have some gladiators, but with real fighting, not like at the munera, and some Greek-style wrestling.

After that it is the turn of that scoundrel, Atticus to be punished," Gracchus said, obviously relishing the word 'punished'.

"How is he to die?" Marcus asked.

"He is to fight, as a gladiator, but for this fight the tables will be turned on him.

At the munera he switched the gladius, so that Ferox got the blunt weapon, and he got the deadly one.

Fir this fight he will find himself in the same situation as poor Ferox, but I don't think that he will be allowed to die quite so easily," Gracchus concluded.

"And who is to fight Atticus?" Marcus asked, intrigued.

"Wait and see…" Gracchus replied, with an enigmatic smile.

When they returned to the editor's box, as Gracchus had said, the remainder of the Ludi consisted of some wrestling, followed by a further display by the young gymnasts who had performed at Gracchus' convivium.

Then there was a gladiatorial contest, in which, after some skillful swordplay, one of the gladiators ended up walking into a slicing swing made by his opponent's gladius, which cut his head neatly from his body. The audience was thrilled, as the headless gladiator, seemingly unaware of his decapitation, took three more steps towards his opponent before thudding to his knees, and then toppling forwards, all the while spraying blood over himself and the sand from his severed neck.

The arena-slaves then recovered the severed head, and the decapitated young gladiator's headless corpse was stripped naked, and dragged out of the arena with ropes round his ankles.

An arena slave then entered, holding a placard, (in the absence of ancient Roman loudspeakers, announcements were usually made by parading a placard round the arena). The placard stated simply that a slave who had cheated and killed a fellow slave was to be punished.

Then, almost immediately, Marcus recognised Atticus striding into the arena.

Atticus looked up at the Editors' Box, and instantly a look of intense surprise crossed his face as he recognised Marcus standing beside Gracchus - and not wearing a slave-collar.

In case you have not been reading The Story of Gracchus consecutively, you need to know something about Atticus. Atticus is a Greek slave-gladiator (his name means 'the boy from Attica', Attica is in Greece). Some time previously Gracchus held a munera in remembrance of the birthday of the Divine Augustus (Divi Augusti). At that munera three pairs of bustuari had fought, the losers being sacrificed in the Etruscan manner. Gracchus had 'arranged' the fight so that selected bustuari would be provided with blunted weapons, thus ensuring their defeat and subsequent deaths. Atticus had secretly swapped over the weapons to ensure that, contrary to Gracchus' plans, he would survive the munera, and Ferox, one of Gracchus' favourites, would die in his place. At the time Gracchus was unable to prevent this from happening, as the munera was considered to be a 'religious' ceremony, however, he subsequently vowed to take his revenge on Atticus. Gracchus had then chosen the day he took Markos to the Amphitheater as the time when Atticus would be punished.

Atticus was equipped very much as he had been for the munera at the villa, with a bulging white loincloth. He carried a gladius, but on this occasion it had been checked before it had been given to Atticus, and it was blunted, and completely useless as a weapon. Whether Atticus knew this or not was a moot point, but regardless, he looked remarkably confident as he entered the arena.

Gracchus had given Petronius special permission to face Atticus in the arena, and Petronius had been given exact instructions as to how to conduct the fight (such as it was).

The senior arena-slave, accompanied by two other slaves, (each carrying a gladius), drew the line in the sand, and the two boys stood either side, waiting for a signal from Gracchus to begin. Atticus and Petronius then began sparring, their swords clashing. After a few moments, Petronius brought his gladius down hard against Atticus' gladius, and Atticus' weapon fractured on impact (this was the result of some work on the gladius performed by 'Vulcan', Gracchus' mute armourer).

Atticus was, as a result, defenceless, and had no option but to sue for mercy, which was exactly what Gracchus had planned.

Of course, Gracchus was not prepared to show any mercy, (just as Atticus had shown no mercy to Ferox).

Atticus was immediately held by two arena slaves, while Petronius stripped the helpless boy of his loincloth. Atticus was partially erect, and his semi-stiff penis, which was dribbling 'pre-cum', jerked suggestively, as he stood facing Petronius.

The question was, was Petronius going to rape Atticus before mutilating and killing him?

Petronius intensely dislike Atticus, and had no inclination to have sex with the boy, and in addition, Gracchus had forbidden Petronius from indulging in such activity in the arena.

Markos was also waiting to see what was going to happen. His feelings for Petronius were such that he was loathe to see his handsome young friend demean himself by having sex in public with the despised Atticus.

"Now, Atticus, if you want this to end quickly and easily, you'd best give us a little performance!" Petronius said gruffly.

"What do you mean?" Atticus asked, looking completely confused.

"Jerk-off and 'cum', here and now, and you'll be finished off quick and clean!" Petronius said, wondering if Atticus would agree to such a demeaning request.

"What? Now? On the sand!" Atticus asked, finding difficult to believe what he was being offered.

"Yes! You're already quite 'hard', so get on with it! The audience is waiting!" Petronius hissed.

And the audience were waiting, restless, and wondering what the two fighters were talking about.

"Alright!" Atticus agreed, "But then just finish me off, quick," Atticus said, sitting on the sand and grabbing hold of his stiffening penis

A murmur went trough the audience.

Atticus probably thought that anything was better than dying immediately, and while he was alive there was always a slim chance of a reprieve, and even if he was to be killed, at least it would be quick and clean, and he would have one, last orgasm, so he started masturbating!

The audience were mesmerised, and Gracchus was surprised that Atticus had 'taken the bait', and was prepared to publicly humiliate himself.

As Gracchus had arranged, however, Petronius had no intention of 'finishing-off' Atticus quickly and cleanly, and he would see that, after Atticus had 'cum', the boy would have plenty of time to rue the day he ever imagined that he could cheat his dominus, and cause the death of one of Gracchus' favourites.

Meanwhile, Atticus, who (as was explained in Chapter X) was disgustingly 'over-sexed', was working hard on his huge, stiff penis.

With his legs spread, the hairy root of his penis exposed, and his heavy, fat testicles jerking suggestively, Atticus made an obscene display of himself, and probably unintentionally provided obvious titillation of the audience.

After a short while it was obvious to everyone one that young Atticus was getting highly 'excited' and very close to an orgasm.

"Oh shit!… I'm gonna fuckin' cum!…" the naked boy groaned loudly, as he jerked his hips forwards and up, in an attempt to further fuck his own fist. By then his hefty balls had pulled up to his hairy groin, and he had started splattering his creamy seed over his sweaty belly.

Having ejaculated on the sand, Atticus was expecting either to be shown 'mercy', and allowed to leave the arena, or (more likely) to be finished off, by either decapitation, or by having his throat cut.

As it turned out Petronius had instructions to take neither course of action.

Two arena-slaves then took hold of Atticus, who was still dribbling spunk from his softening cock, and laid him on his back.

"What?" Atticus managed to grunt, confused by what was happening.

"There's my spunk!" Atticus shouted.

"So you said you would end it… after I spunked!" Atticus insisted.

***

WARNING:

the following paragraphs are focused on a gory execution

If you don't like that, go directly to the conclusion

***

The slaves then each grabbed one of Atticus' legs, spread them, and then, lifting them up, pulled them over so that Atticus (on his back) had his ankles either side of his head, by his shoulders. The boy was literally 'folded over', with his naked backside exposed.

"Please!… No!…" Atticus pleaded, thinking that he was probably going to have his arse fucked, probably by the two arena-slaves and Petronius.

Petronius was then handed a pilum (javelin) by another arena-slave.

"Oh no! Not that! …Please don't spear me!… Please!… Mercy!…" Atticus cried out.

"You didn't show any mercy to Ferox, and he was castrated and decapitated, so … no mercy will be shown to you!" Petronius said quietly and coldly.

The hushed audience waited to see what would now happen to the naked, helpless boy.

Markos watched intently, interested to see how resolute Petronius could be.

On his back on the sand, in an appallingly ignominous position, Atticus' anus was fully exposed, and Petronius, cruelly let the tip of the javelin rest on the trembling boy's quivering 'hole'.

"No!… Don't spear me there!… Don't' stick it up my fuckin' arse-hole!" Atticus groaned, as he stared at his now stiff jerking penis, which was dribbling clear liquid onto his chest.

Petronius ignored the pleading boy, and began pressing down. The javelin tip immediately began to open up Atticus' anus and blood began to trickle down between his muscular buttocks.

"Fuck!… " Atticus squealed.

Petronius pressed down harder. and the large head of the javelin disappeared inside the squirming boy.

"Shit!… You cunt! It's in my guts!…" Atticus screamed as his hips rose up automatically, and he inadvertently impaled himself on the spear.

Petronius then leaned on the shaft, and the javelin passed right through Atticus' torso, deftly missing his spine, and emerging from his straining back, fully impaling him.

Here, a brief explanation is required: While Gracchus' Amphitheater had been temporarily closed, the arena floor had been renovated. The floor of the arena was covered with sand (hence the name, harena, meaning sand in Latin). More sophisticated amphitheatres, like Gracchus' Amphitheatre, had the sand laid on a wooden floor. The wood, of course, when liquid passed through the sand, would eventually start to rot, hence the renovation. The wooden floor itself was laid over voids, which allowed for storage, and the installation of trap-doors, lifts etc. The wooden floor also allowed for the stable securing of structures on the sandy arena surface. In the case of the appearance of Atticus in the arena, the wooden floor would serve another purpose…

"Fuck!… No!…" Atticus moaned helplessly, as he was held firmly by two of the arena-slaves.

Petronius then called over another arena-slave, and together they both pressed heavily of the metal javelin shaft, forcing it deep into the wooden floor of the arena. The result was that Atticus was not only impaled through his ripped and ruined anus, but was also pinned helplessly to the arena floor. Then Petronius draped Atticus' tiny white loincloth, along with his white leather waist belt, now no further use to the naked boy, over the butt of the pilum.

Petronius then stepped back, looking down on the trembling, sobbing naked boy.

"Now you can stay there…and suffer!" Petronius said, his voice expressionless.

"No …Please!… Help!…" Atticus moaned.

Petronius then walked away, to some polite applause from the audience, and the arena-slaves let go of Atticus, as the boy was now firmly and helplessly attached to the arena floor. There was nothing that Atticus could do.

There was very little external bleeding, but his penis, which had become flaccid, after he had masturbated himself to orgasm, had now stiffened, and become enormously erect, as a result of his anus and rectum being penetrated. (The ultimate public humiliation for an adult Roman male, even a slave). It was not, however, a sexual arousal, but simply an automatic, physiological reaction, accompanied by regular spurt of glistening semen. At the same time his legs started to tremble, and then develop spasms.

Interestingly, Petronius seemed to be in no hurry to 'finish-off' the unfortunate lad, and he called for the next contest, to start, which was to feature two naked pancratium wrestlers.

So, as the wrestlers grabbed the attention of the audience, poor naked Atticus was simply left, humiliated, and moaning in agony, helplessly pinned to the sand.

The ludi went on for another hour, and Atticus remained all that time in the arena, moaning and sobbing, with his legs twitching spasmodically, occasionally dribbling spunk and pre-cum, and spraying urine. While he was pinned to the arena floor, Atticus' penis had become enormously engorged as a result of the large bulk of the javelin shaft, which had horribly stretched his anus and rectum, and his foreskin had been forced back, exposing his dark, gleaming 'glans'.

Romans and Latins, like the Greeks, were by tradition always uncircumcised. While male nudity was accepted completely by the Greeks, and to a lesser extent by the Romans, and normally considered acceptable for slaves, if not citizens, the exposure of what the Romans referred to as the 'glans', (literally in Latin, 'acorn'), was considered the ultimate obscenity, as it was associated with sexual activity.

For the audience, who were seated well above Atticus, it was possible to look down, and observe his 'privates' between his legs, and his unnaturally engorged, twitching penis, with its exposed 'glans', and his horribly swollen testicles, which were objects causing considerable amusement, titillation and arousal for those watching.

However, as the ludi had come to an end it was time to be rid of Atticus. Petronius approached the naked, groaning boy.

"Well …Atticus… Do you remember, at the munera, saying to Ferox, 'What's it feel like, Ferox?', after he had his balls cut off? Well now you're gonna find out, boy, except that you're gonna have you cock cut off as well!" Petronius said, with a grin, as he bent over the squirming by.

Petronius then unsheathed his vicious looking, ivory handled castration knife.

Ironically, the handle of the curved castration knife was in the shape of an fully erect penis, with the 'glans' exposed, and the pommel was carved in the form of a scrotum, containing two bulging testicles. The curved blade of the knife was not only designed to facilitate the removal of penis and testicles, but was also ideal for slicing open the belly, as part of the process of disembowelling.

"No please!… Not my bollocks!…" Atticus groaned.

There was an odd pause.

"I'm sorry!… I'm sorry for what I did to Ferox… really! But just spare me!…" Atticus screamed.

Finish me quick, but not my balls an' my cock!… Please!" the naked boy begged as he squirted yet more spunk.

"Too late for that!" Petronius replied.

With that he grabbed hold of Atticus' bulky genitals.

"No!…" Atticus screamed, as Petronius sliced through the hairy root of Atticus' bulky genitals.

Atticus squealed hysterically.

"What's it feel like, Atticus?!" Petronius asked, coldly.

"F-u-c-k!…" was all that Atticus could reply, as his whole body jerked spasmodically.